Cypriot traditions are an intriguing mix of ancient values, church customs, folk beliefs and superstitions. At first, they might seem a bit weird, but once you learn their history, it's pretty easy to understand their logic.

In this article, we'll look at what 'philoxenia' means, why you should break a pomegranate on New Year's Eve, and what to do if you lose something.

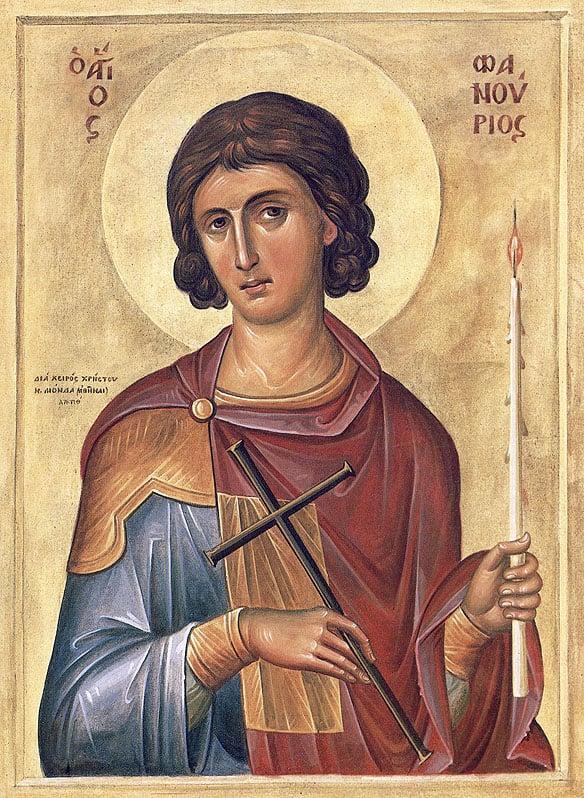

Here's a recipe for Saint Fanourios cake.

So, what do we normally do when we lose something? Do we panic and try to find it, and if we can't, do we just accept that we've lost it? But not in Cyprus. Well, here, people usually turn to Saint Fanourios for help. We don't know much about the life of this saint. He was only discovered in the 16th century, and it was a pretty interesting discovery.

It happened in 1500 on the island of Rhodes in Greece, during the time when the Ottomans were in charge. At that time, they were trying to strengthen the city's outer walls using stones from older buildings, including a beautiful ancient church. There were lots of icons left in the ruined church, but almost all of them were in a terrible state, and only one of them looked like new. It was a saint we didn't know about, but his name was on the icon — Fanourios, and around the edge of the icon there were 12 small images showing the saint's life. As it turned out, he was a martyr. The name Fanourios comes from the Greek word (φανερώνω), which means 'to appear' or 'to reveal'.

Thanks to this amazing turn of events and his name, the saint soon became the patron saint of all lost things: not only objects, but sometimes even people. Saint Fanourios is a really important figure in Greece and Cyprus. His feast day is on 27 August. On this day, everyone brings a special sweet pie to the church to honour Saint Fanourios, which is called 'fanuropita' here. Once it's been blessed in the church, it's given to everyone who comes. But you don't have to wait for Saint Fanourios' day to turn to him. If you've lost something, you've got to bake a "fanouropita" at home, read a special prayer to Saint Fanourios, and then give the pie to as many people as possible. Then, you just have to wait for the saint to help you find what you've lost. Some people think it's better to give it to at least three couples who've never been divorced, but that's just a folk belief. The cake is a breeze to make. You'll need:

- You'll need three cups of flour.

- One cup of sugar, please.

- You'll need about ¾ of a cup of olive oil.

- One cup of fresh orange juice should do the trick.

- You'll need one tablespoon of baking soda.

- Just a teaspoon of vanilla, please.

- Just a teaspoon of cinnamon should do the trick.

- You'll need half a cup of chopped walnuts.

- Just a squeeze of half an orange.

First, mix all the dry ingredients together – flour, sugar, baking soda, cinnamon and nuts. Then add all the liquid ingredients: olive oil, vanilla, orange juice and orange zest. Give it a good mix. Then put the mixture in a greased baking tin. Pop it in the oven for 40-45 minutes at 170 degrees.

Lots of people from Cyprus will tell you that Saint Fanourios is great at helping people find lost stuff. He's one of the island's most popular saints, and 'fanouropita' is a delicious, spicy cake that's hard to resist.

Pomegranates are a symbol of prosperity and more.

Pomegranates in Cyprus are more than just a fruit or a tree. They're an age-old symbol of fertility and prosperity. Pomegranates didn't originally grow in Cyprus, but references to them date back to the 13th-14th centuries BC. Cyprus has always been seen as the centre of the cult of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and fertility. Legend has it that it was the mythical goddess who first planted a pomegranate tree on the island. Since then, pomegranates have been seen as sacred.

On the one hand, pomegranates were linked with life, abundance and fertility, as well as female fertility. There are lots of archaeological finds with decorative motifs in the form of pomegranates in jewellery, ceramics, sculptures, mosaics and frescoes that prove this. But its bright red juice, which looks a bit like blood, and its white, bone-like partitions, made it a symbol of the afterlife.

They found loads of objects in tombs in the Kition and Kourion areas dating back to the 13th and 15th centuries BC, like sceptres and jewellery with pomegranate motifs, as well as glass figurines of pomegranates. So, it's no surprise that the pomegranate was a really common motif in Cyprus during the Bronze Age.

When Christianity arrived on the island, the pomegranate symbol took on an extra meaning. It came to be a symbol of hope for resurrection and eternal life. The many seeds of the pomegranate, all gathered in one fruit, represent the unity of believers in Christ, as well as the gathering of numerous saints. Just like the seeds of the pomegranate, all believers make up one church, one 'body of Christ'.

In ancient times, the pomegranate was seen as a symbol of sensuality and fertility. But when Christianity arrived on the scene, its red colour started to be linked with purity and innocence. You often see the pomegranate pattern in church decorations and paintings, especially of the Virgin Mary. Take the name of the famous Cypriot monastery 'Panagia Chrysorotissa' for example. This literally means 'Mother of God of the Golden Pomegranate'. You'll also find pomegranate patterns on church utensils, frescoes, capes and priests' vestments. They represent spiritual growth and are a reminder of Paradise.

Even today in Cyprus, there's a tradition of adding pomegranate seeds to 'kolivo' — a ritual church offering consisting of boiled wheat, almonds, sesame seeds and raisins. The sweet red seeds of the pomegranate represent hope for resurrection and eternal life. Kolivo is used both on holidays (name days) and on days of remembrance of the deceased.

And the tradition of breaking pomegranates on New Year's Eve is still going strong. On New Year's Eve, the whole family goes outside and turns off the lights. At midnight, one of the family members will break a pomegranate on the porch or front door of the house. It's thought that if you scatter more seeds, you'll be more likely to have more money and luck in the New Year. Usually, it's the kids who get to collect the seeds that have been scattered around.

Pomegranates are also often used in wedding ceremonies. If you're a newlywed, you'll probably be given a gold or silver pomegranate as a symbol of a happy marriage, prosperity, well-being and a large family. These kinds of pomegranates are usually passed down through the generations. It's a bit like the New Year's tradition, where they break pomegranates at weddings. This is usually done outside the house of the newlyweds. It's thought that if you scatter more seeds, the new family will be richer and happier, and have more children.

Today, the pomegranate is still a symbol of Cyprus. Jewellery, ceramics and patterns featuring pomegranates have been popular on the island for thousands of years. The fruit itself is a real treat for the locals.

So, let's talk about wedding customs.

Cyprus has had rich wedding traditions for centuries. In the past, weddings were a big deal for the whole village and were the main event, with loads of complicated and long rituals that lasted for days. While modern life has influenced wedding traditions, the main customs have been kept alive and are still a thing today. The celebrations usually last three days and consist of 'i paramoni' (the eve of the wedding), 'o gamomos' (the wedding itself) and 'o antigamos' ('instead of the wedding' — the final day of the celebrations).

Before the wedding, the bride and groom stay in their homes and don't see each other until the wedding itself. The groom's mates and family get together at his place to do the 'shaving of the groom' thing, with local tunes like violins and lutes playing, plus jokes and songs. Then there's another interesting ritual – the 'wedding dress dance'. The bride and groom's clothes are put in a special basket and covered with red cloth. Then, the clothes are blessed by burning incense. This is done either by a priest or the groom's mother. There are three women and three men, and they take it in turns to pick up the basket and dance with it, making three circles around the groom or bride. Then it's time for the 'dressing of the groom and bride' ritual. Usually, the best man helps the groom get dressed. The bride is helped by her maid of honour and other women to put on her veil and jewellery and to have rose water sprayed on her.

Then, there's a ritual called 'zosimo', where the bride and groom symbolically say goodbye to their family home. The parents of the bride and groom bless them with a special red belt, first making a cross on their foreheads or chests, and then tying it three times around the waist of the bride and groom. This ritual can also be performed by other close relatives, but make sure there's an odd number of them. The priest can also take part in the ceremony. The red colour of the belt signifies the purity of the bride and groom, and the untying of the belt symbolises the transition from virginity to married life. People also thought that the colour red protected against the evil eye and was a symbol of fertility. So, at the end of the ritual, the mother of the bride usually burns incense over the heads of the bride and groom three times.

Most Cypriot weddings tend to be church weddings. Then at the end of the ceremony, everyone gathers in a tavern for a lively and fun feast. In the past, it was traditional to attach banknotes to the bride's dress during the dance, but now it's more common to give the newlyweds an envelope with money. As a special treat, each guest will receive a beautifully wrapped sweet called 'loukoumia tou gammou'.

So, let's talk about how we do christenings.

For Cypriots, christening is the most important event in the life of every person. Most people in the south of the island are Orthodox Christians, and religion is a big deal here.

There are some pretty interesting customs connected to childbirth in Cyprus. For example, it's thought that for the first 40 days after birth, the baby should stay at home and not be seen by strangers. So, not all families, especially religious ones, take the newborn outside the house for 40 days. It's a common belief that babies are particularly vulnerable during the first 40 days of life, so to protect them from the evil eye, they're not shown to anyone. Then, after that, the baby is taken straight to the church so the priest can say a special prayer over it.

But first, the priest takes the child in his arms and brings him to each icon in the church. It looks pretty touching from the outside, like the baby's being introduced to all the saints on the icons. Once the prayer's been said, we can sort out a date for the christening. This normally happens 2-3 months after the child's birth. The whole extended family is there for the christening, and then afterwards they usually all meet up in a tavern or a banquet hall. At a wedding, it's traditional to give the parents an envelope with some cash, and they then give the guests a special sweet treat. Most often, this is almond biscuits in beautiful wrappers.

So, according to Cypriot tradition, it's pretty common for kids to have the same name as their grandma or grandpa. That means that a lot of relatives in the same family might have the same name. Most of the time, these are the names of saints who become the child's patron saint after baptism. But in Cyprus, there are some pretty unusual names too, like Sotirula (Sotiris), which comes from the word 'savior,' as well as Panayota (Panayotis) and Despina, which are connected to the Virgin Mary.

Philoxenia (hospitality)

In Cyprus, hospitality isn't just about being polite. It's a sacred tradition that's been around for thousands of years. The Greek word 'philoxenia' (φιλοξενία) literally means 'friendship/love for strangers' or 'hospitality'. This tradition actually goes way back to ancient Greece, to the time of the cult of pagan gods. The main one was Zeus, also known as the 'protector of travellers'. It's all part of a legend about Zeus and Hermes, who pretended to be poor travellers. They kept knocking on doors until an elderly couple opened their door. In return for some grub and a roof over their heads, Zeus turned their shabby house into a fancy mansion. Since then, the ancient Greeks believed that any traveller or unexpected guest could be Zeus and should be given the best welcome. The ancient philosophers and poets were big on 'Philoxenia', as you can see from Ovid's poem "Metamorphoses" for example. So, in ancient times, Cypriots strictly followed the tradition of 'philoxenia'.

Then, when Christianity arrived on the island, the idea of 'philoxenia' took on a new meaning. 'Philoxenia' is one of the main Christian virtues, combining love, willingness to sacrifice something for one's neighbour, and to come to their aid. They started seeing Christ in every guest and following the Gospel commandment to share the last with their neighbour. In the past, people in villages were always happy to take in a stranger, give him a place to sleep and treat him to everything they had. Even now, especially in small mountain villages, you can still experience a bit of this hospitality.

It's not uncommon for an older lady to invite you into her home and treat you to some Cypriot coffee, a glass of cool water and 'glyko tou koutaliou' (γλυκο του κουταλιου), which literally means 'sweetness in a spoon'. It's usually fruit or walnuts cooked in syrup - a bit like jam but with a sweeter taste. This has been the standard treat for travellers in Cyprus for centuries. People thought that cold water and sweet stuff would help you to quickly get your strength back and cool down on a hot day, while strong coffee would give you a boost. Every housewife always has a supply of jars with 'glyko tou koutaliou' for such occasions.

But even in cities, Cypriots follow the tradition of 'philoxenia'. They're super welcoming and always happy to help. Local people are always happy to invite you to their family celebrations or Sunday lunch, and you'll be made to feel like one of the family. It's also common here to treat each other. Local housewives love to share their culinary delights, not only with relatives or neighbours, but also with people they don't know very well. It's fair to say that Cypriots are all about 'philoxenia'.

Read also: