When you first get acquainted with Cyprus, you read a guidebook and suddenly find out that the island belonged to the Romans or Greeks and was under the rule of the Venetian Empire for a long time.

You expect to see here at least the same beauty as in Italy. But the reality regarding the preserved heritage is somewhat disappointing.

Where are the beautiful palaces? Where is the marvelously fine gold Assyrian jewelry? On excavations we are met only with the wreckage of beautiful buildings and extraordinary work, miraculously preserved mosaics.

The truth is that Cyprus, the treasury and seat of several of the richest civilizations, was the victim of several devastating earthquakes, and then was mercilessly plundered in the 19th century. The name of the plunderer is well known to all.

In 1879 he became the first director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

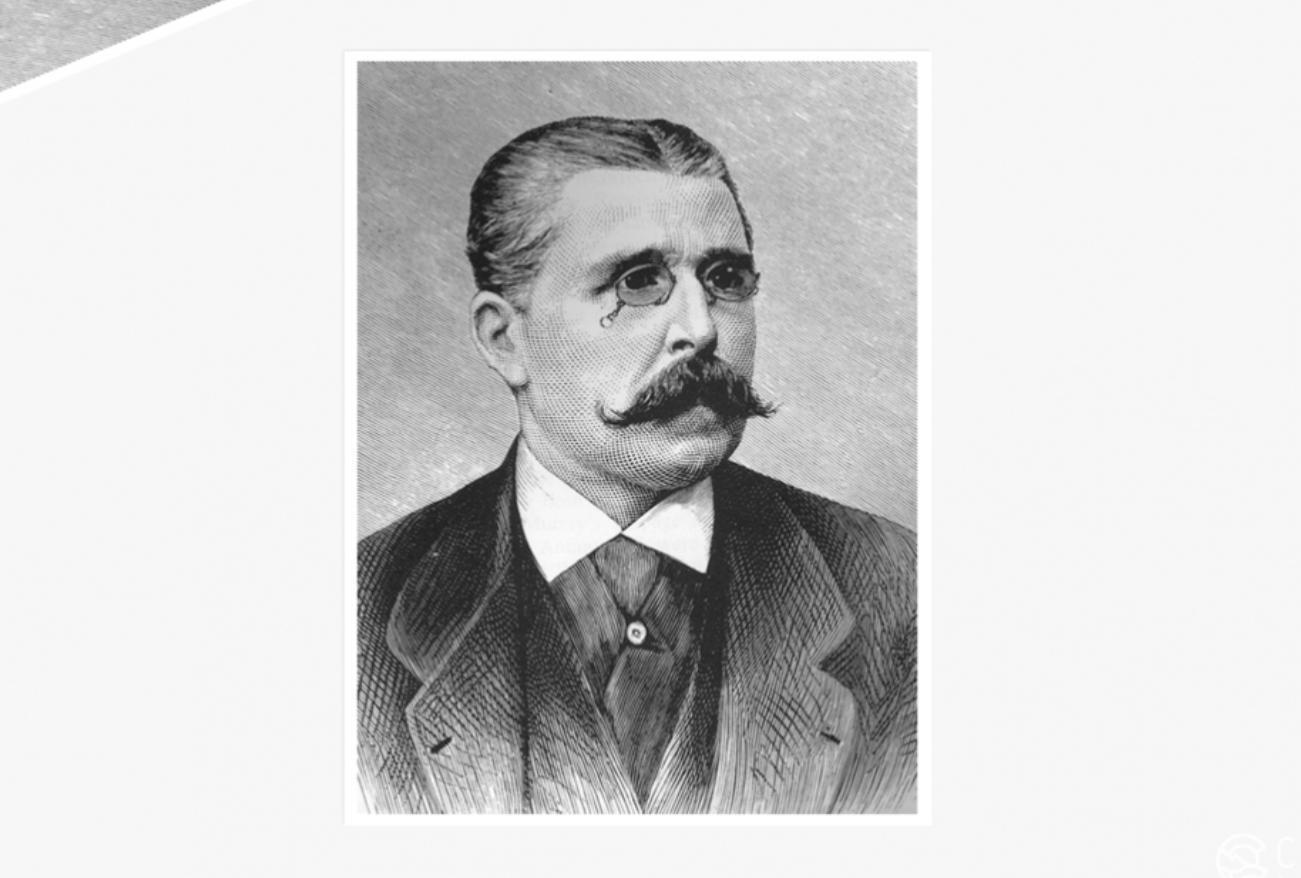

In 1878 he published the book "Cyprus. Ancient Cities, Tombs and Temples". From 1864 to 1877 he was the American consul in Cyprus. His name was Luigi Palma di Cesnola. About his turbulent and changeable fate, multiple seasons of series can be filmed.

Luigi was born on the territory of modern Italy, near Turin, on June 29, 1832, in a noble family. He participated in the Austro-Italian War or, as it is also called, the First Italian War of Independence. At the age of 15, Luigi was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant. After some time he sailed to Istanbul and then joined the British army and fought against Russia in Crimea.

Afterward, Luigi moved to the other side of the Atlantic and tried to start a new life in America.

When he turned 26, the young man tried to teach Italian and French in New York. But life did not please him. Luigi was accompanied by constant failures, because of which he almost committed suicide.

In 1861, the American Civil War broke out, and Luigi fought on the side of the North, was wounded, and captured by the South, for which he later received the Medal of Honor. In 1865, the war ended and Luigi went into the U.S. Foreign Service. He was given an American passport and in the same year was sent as consul to Larnaca in Cyprus, which at that time was part of the Ottoman Empire.

On the island at that time Cesnola found devastation. Cyprus seemed to him a real backwater, and the population - barbarians. Without thinking for a long time, the man decided to take the treasures of Cyprus to civilized countries to sell them for profit.

It should be noted that Luigi Cesnola was not a professional archaeologist or historian. Therefore, he conducted excavations like a barbarian, destroying early archaeological layers without making proper classifications of the found collections.

As American consul, Cesnola received permission to excavate in Constantinople. Using the official permission, in his own words, within 10 years he found 2,310 coins, 14,240 vessels, 2,110 statues, 138 tomb steles, 4 carved sarcophagi, 1,090 valuable stones, and other precious artifacts. Despite his complete ignorance of the process, Cesnola was very lucky in archaeology. Wherever he started excavating, burial caves, temples, vases, statuettes, and sarcophagi were discovered.

Interestingly, it all started with the tombs in Larnaca, not far from Luigi's residence. The diplomat-archaeologist quickly immersed himself in Cypriot antiquities, took a detailed interest in Cypriot history and hired himself several hundred shovel diggers.

In 1867, satisfied with his research in Larnaca, Luigi turned his eyes to Curium and conducted a series of excavations in this ancient city.

This is how the so-called Curium treasure was found - jewelry and other items made of gold, silver, bronze, and copper. Why so-called? Because Luigi, who was not a professional archaeologist even by the standards of the XIX century, wanted to make a beautiful fairy tale out of science. Therefore, archaeological finds of different times, finds that were not related to each other in any way, were united under some false and deceptive concept of "treasure".

At the time, Cesnola's only concern was, in his own words, to compete with Heinrich Schliemann.

He wrote: When I publish my latest finds, they will forever eclipse Schliemann's," Cesnola declared.

It should be mentioned that the ambassador had only permission to excavate, however, the export of archaeological finds was strictly forbidden. Despite this, Cesnola still took out the treasures by stealth. Eventually, his collection reached the shores of North America and was bought for 1 thousand dollars, and then became one of the fundamental collections of the then-new New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. The catalog of the Palma di Cesnola collection, which describes approximately 6,000 objects, can be viewed on the museum's website.

The catalog features approximately five hundred works from the collection, illustrated with superb color photographs.

Dating from around 2,500 BC to 300 AD, these works are among the finest examples of Cypriot art from the prehistoric, geometric, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Among the objects are: monumental sculptures, weapons, tools and domestic utensils, vases, lamps and ritual paraphernalia, sacred statuettes, engraved seals, jewelry and luxury goods.

They represent all the basic materials worked in antiquity: stone, copper-based metal, clay, earthenware, glass, gold and silver, ivory, and semi-precious stones. These works testify to a typically Cypriot mixture of local traditions and elements assimilated from the ancient Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans, who one by one controlled the island. Of particular note is the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection of Cypriot limestone sculptures, which includes impressive sarcophagi from Golgoi and Amathus and is the finest in the world.

Luigi Cesnola was director of the museum for 30 years and lived in wealth and honor until his old age. He became the most massive plunderer of Cyprus but by no means the only one.

The pioneer of treasure hunting in Cyprus was an Englishman, Alexander Drummond. He was the British consul in Syria, but along the way several times visited Cyprus with a "special mission", and surveyed the island from the point of view of replenishing the antique departments of British museums.

Several halls of the British Museum now exhibit the treasures of Cyprus. In 1862, with the support of the French Consul, a large number of slabs with ancient Greek inscriptions and many other finds were sent to the Louvre. In spite of all of the above, some of the treasures of Cyprus can still be seen in the Museum of Architecture in Nicosia. For example, part of the famous terracotta army.

Read also:

- Cypriot Wineries: Where to Taste the Nectar of the Gods on the Island?

- How to Become a Tax Resident in Cyprus

- 7 Facts About Ecology in Cyprus

- Holidays in Limassol: Top 10 Exciting Ideas for Tourists

- Self-employment or a company in Cyprus: which type of business to choose?

- How to Develop an Earning Strategy with Cypriot Real Estate?